Exotic dark matter theories. Gravitational waves. Observatories in space. Giant black holes. Colliding galaxies. Lasers. If you're a fan of all the awesomest stuff in the universe, then this article is for you.

Dark Matter and the Dwarf Galaxy

Most of the contents of our universe are of a form completely unknown to physics. That's just a raw fact that we're all going to have to get used to. If you're tempted to think that it's just some sort of

cosmological

problem, an issue that only arises on the very largest scales, well then I have bad news for you. One of these mysterious components to the cosmos is - as far as we can tell - a form of matter.

But not just any form of matter, otherwise we would've seen it by now. No, we think it's a kind of

dark

matter;

matter that simply doesn't interact with light

. No emission. No absorption. No scattering. Nothing. And the fact that dark matter exists shouldn't be

that

surprising, should it? After all, who dictated that everything in the universe

must

interact with light?

Nobody did, and so here we are. If you look at a random galaxy, the stuff that lights up - stars, nebulae, etc. - only represent a small fraction of the total amount of mass in that galaxy. The exact ratio between "normal" matter and the dark stuff depends on lots of factors, like the galaxy's formation history. But in general, the smaller the galaxy, the more of it is dominated by dark matter.

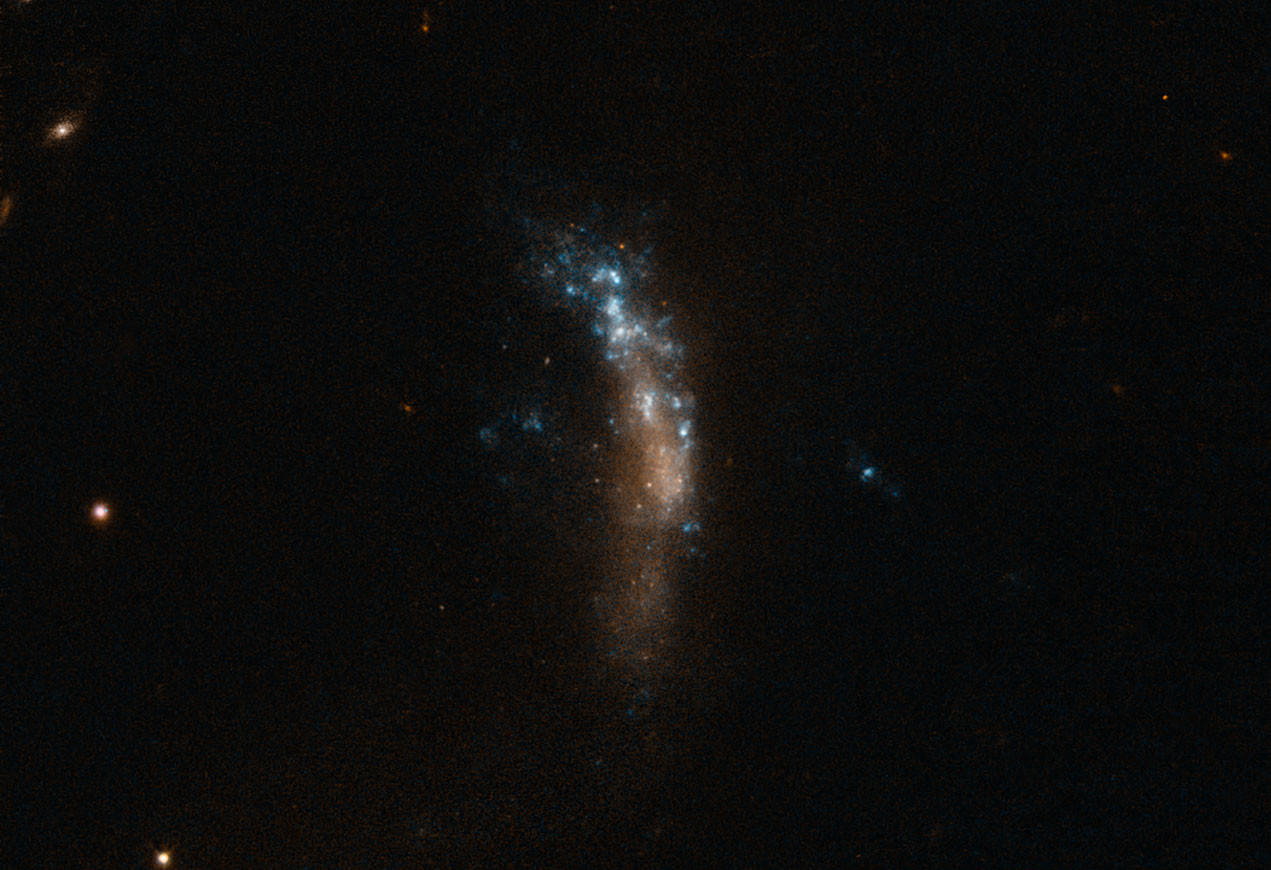

[caption id="attachment_113174" align="alignnone" width="1271"]

Small, dim, and dark: the dwarf galaxy UGC 5189A. Image Credit: ESO[/caption]

The smallest galaxies, known as

dwarf galaxies

, could provide a handy laboratory for studying dark matter. In these galaxies, dark matter is free to do what dark matter does without any of that pesky light-interacting-matter to really complicate things. If dark matter does something strange (well, stranger than simply existing), like interact with itself via the weak nuclear force, or be composed of multiple kinds of exotic particles, then any effects will make themselves more pronounced in a dwarf galaxy than something like the Milky Way.

This is all great and good, except for the small caveat that while all these interesting physics are happening under the hood, it's hard for us to see it. Because it's dark.

The Black Hole Connection

One thing of the many things that we don't understand about dark matter is how it behaves in the cores of galaxies. Simple

simulations of galaxy evolution

predict something called a "cusp" - a hard nut of incredibly high density sitting in the otherwise creamy center of a galaxy. But observations do not bare this out: there ought to be a lot of stars following the gravitational influence of all that dark matter. And there sure are a lot of stars in the center of a galaxy, but not

that

many.

Something has to

smooth out the central dark matter

. It could be exotic interactions in the dark matter itself. It could be more mundane causes like supernovae winds blasting out the gas. It could be both, or neither.

[embed]

Astronomers are very, very interested in the cores of galaxies, and especially dwarf galaxies, because it's there that they can potentially learn a lot about dark matter. And despite their complicating, messy physics, we still need stars and gas to observe, probe, and study the dwarf galaxies, hoping that we can trace the behavior of the underlying dark matter. But

dwarf galaxies

are far away, dim, and small - and their cores even more so.

How could we possibly peek inside them?

Thankfully galaxies have more than stellar citizens. They also have black holes. Giant

supermassive ones in their cores

and millions of smaller ones floating within them. And the fact that giant black holes tend to congregate in the cores of their host galaxies might be useful. So perhaps - work with me here - if we could somehow study the behavior of the black holes inside dwarf galaxies, we might get some clues to the nature of dark matter.

LISA Hears in the Dark

But black holes are also black and hard to see. And small. And far away. Fortunately, we don't have to see black holes - we can hear them.

When black holes collide, they quake and distort the fabric of spacetime so much that they cause waves, like ripples spreading out from a heavy stone dropped into the water. These waves of gravity spread throughout space at the speed of light, ever-so-slightly stretching and squeezing any intervening matter as they wash by. In fact, your body is, as you read this, being tugged and pressed like a piece of putty from the innumerable gravitational waves passing through the Earth.

These waves of gravity are insanely hard to detect, which is why the first people to measure them got

some Nobel prizes for their decades-long effort

to use interfering beams of light to capture the subtle signal.

[embed]

But our

three gravitational wave observatories

on the surface of the Earth can't help us with our black-hole-inside-dwarf-galaxy-to-study-dark-matter problem. Those black holes - known as

intermediate-mass black holes -

are too small to make a detectable signal way over here in the Milky Way when they merge.

But a gravitational wave observatory in space could. The

proposed LISA mission

(which stands for, as you might've guessed, Laser Interferometer Space Antenna) might have the right sensitivity to see the signal of merging medium-sized black holes, just like the ones found in the hearts of dwarf galaxies.

And according to a

new paper recently accepted by the Astrophysical Journal Letters

led by Tomas Tomfal of the University of Zurich, different models of dark matter (and its possible interactions with the normal light-loving kind of matter) can influence how often and how quickly the black holes in dwarf galaxies merge, which is something that LISA can possible pick apart.

It's a roundabout path to understanding dark matter, but in a problem as vexing as this, it's a promising one.

Read more:

"Formation of LISA Black Hole Binaries in Merging Dwarf Galaxies: the Imprint of Dark Matter"

Universe Today

Universe Today